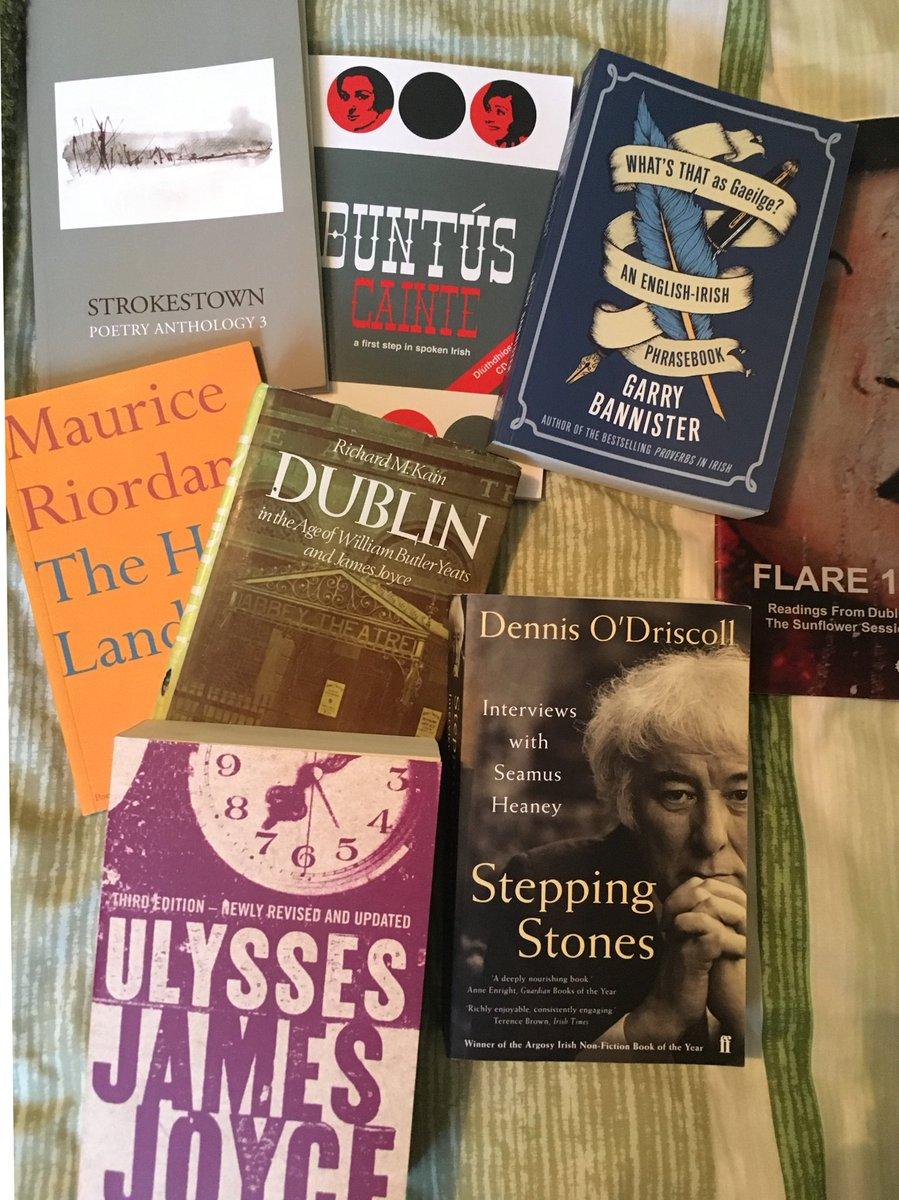

Shoulder Tap by Maurice Riordan review – a wry look in the mirror

Maurice Riordan, in one of his poems, describes a “shoulder tap” as a practical joke. I was not altogether sure what this amounted to until YouTube put me straight – the sneaky touch on a shoulder that leaves the tapped one disconcerted, as they look around to find that there is no one there. Memory itself is the shoulder tap of this collection: the past steals up without warning in often discombobulating bids for attention. In the title poem, it is a boyhood friend Riordan recalls – dead now – who plays this sad prank on him. This is Riordan’s fifth collection in a distinguished career and is finely attuned to the past: he was born in County Cork and his rural Irish roots are still much in evidence.

In Madame Bovary, a single memory recalls his youth, and what particularly pleases is the poem’s assured lack of commentary, an underwritten composure that only comes, if you are lucky, with maturity. Riordan’s rogue father heads off on a drinking spree or, in Irish parlance, a “batter” (I had to look that up too). But the most significant thing here has to be the fading volume of Madame Bovary on the windshield. It exists like a promise: one feels confident that Riordan will have eventually picked the Flaubert up before launching himself upon the literary life.How do you judge where you find yourself in a life? In the entertaining Hamartia (meaning: the flaw that leads to a hero’s downfall), a nameless woman turns on Riordan in scornful criticism of his work. She denounces his “fixation on the local” and “Those litanies of place names.” And it goes further downhill from there:

And besides you’re stuck in some wormhole.Band names. Brand names. Dead girlfriends.You can only drink out of a straight pint glass.You can only sleep on clean white sheets.You boil pigs’ feet and eat Golden Wonders in their skins.Nothing’s to your liking unless you had it moons ago.

The song of the has-been, it pulsates with reckless comedy:

Her index finger is prodding my ribcage.Gently now, as though I’m an endangered species.You’re a throwback, a quisling, a swipe left, a a aI’m nodding again. At everything she has to tell me.

Undeterred, Riordan’s project is, in part, to see what a “selfie”, in a less trivial sense, might mean in his 60s, at an age where posing is past the point. He is aided by a dextrous imagination and gift for self-ridicule. In The Narcissist, he writes about his interior self-image before owning that:

Whenever I’m caught off-guard, in a hotel or new bedroom,it comes as a shock I’m in the presence of another male,who is florid and badly proportioned.

You might side with the finger-prodding critic here. You might ask: who cares? But this would be to miss the point. Riordan’s exploration of the oddity of finding yourself one person and not another is a universal experience. And there are tremendous poems on other subjects too: a storm and its fallout, a sheltering fledgling, an unusually erotic game of Monopoly. But the best are about identity at its most mysterious. The Changeling is an especially arresting piece about the elusive self:

I thought you can hide in galleries and foreign cities,in bars in daytime, even in a swimming pool.There are hours you can spend loosely tethered to a lover.

That “loosely tethered” is perfection. Riordan is an exceptionally accomplished herdsman of words, corralling the unexpected into a single field and stoically soaring above his own doubts.

Madame Bovary

I’m following the old man out to Clonmult.That’s him bareback on the mare, his headin a cloud of hawthorn, taking her to stud.I’m in the Morris behind, stallingand starting, with Madame Bovarypropped open on the dashboard.

Nance, the mare, is my small sister, hand-reared with the Pyrex bottleand rubber teat I’d barely surrendered.In the paddock, the black stallion is upon his hindquarters, wielding his yardlike it’s a length of plastic hosepipe.

Now it’s done, we switch roles –that’s me on Nance belting for home,while my father is gone to the Easton his travels, off on a batter,Madame Bovary at Chapter Twelve,yellowing under the windshield.