How Practical Is Harvesting Water From The Air?

Water is one of the most precious substances required to sustain human life. Unfortunately, in some areas like California, it’s starting to run out.

The ongoing drought has some people looking towards alternative solutions, such as sucking water out of the very air itself. In particular, a company called Tsunami Products has been making waves in the press with its atmospheric water generators, touting them as a solution for troubled drought-stricken areas, as reported by AP News. Today, we’ll look at how these machine capture water, and whether or not they can help in areas short on water.

A Condensed Explanation

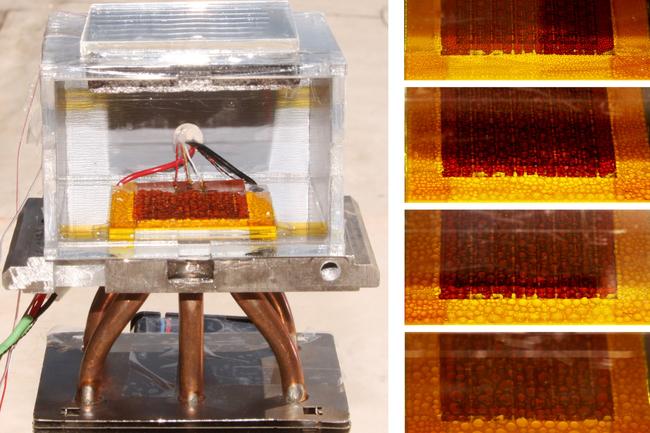

Systems such as those built by companies like Tsunami Products are referred to as atmospheric water generators of the cooling condensation type. They work on much the same principle as a modern air conditioner, relying on a refrigeration circuit. The refrigeration circuit is used to create a cold surface upon which water from the air condenses and is collected. From there, the water is filtered and purified to remove any viruses, bacteria, or other contaminants that may have been captured from the air.

It seems straightforward enough; the basic principle at play is quite simple. Collect water that condenses on a cool surface, filter it, and drink it! However, there’s a reason that we don’t typically look to the air itself as a source of water. That’s because of the energy cost, which is, in a word, significant. Essentially, running such a machine is functionally equivalent to running a large air conditioner.

For example, the smallest unit offered by Tsunami Products is the Tsunami 500, which costs on the order of $30,000 and is reportedly capable of delivering up to 204 gallons (773 liters) of water per day. That’s a lot of water, approximately enough to cover the daily needs of two Americans – 82 gallons of water each. To capture that water, the Tsunami 500 uses an astonishing 5.8-7.5 kilowatts, depending on ambient conditions of temperature and relative humidity. Multiply that out over 24 hours, and that water came at the cost of 139.2-180 kilowatt-hours. Looking at the best case, that’s around 0.68 kilowatt-hours per gallon. In comparison, desalinating seawater, which is already considered energy-intensive, can be done for just 0.0113 kilowatt-hours per gallon.

What if We Use Renewable Energy?

For those with solar panels and battery storage, the energy cost may not seem like a problem. However, for those stuck paying grid prices, such an installation in drought-struck California would cost on the order of $27-36 a day to run, given the current energy price of around 20 cents per kilowatt-hour. It’s a huge price to pay for water, given the average bill in California currently sits at just $65 a month.

The key really is pairing such technology with solar power, in order to avoid contributing further to the climate change problem that causes hot weather and droughts in the first place. Bay Area man Don Johnson lives in the city of Benicia, and bought himself a Tsunami 500 in order to supply his garden’s water needs. However, he found that the machine was able to generate more than enough water to cover both his garden and his household usage. With the benefit of a large solar install on his roof, Johnson hasn’t had to deal with excessive power bills when running the system.

Such products are marketed as a useful way of generating water in places where there simply is none, outside of the humidity in the air itself. They can indeed do that, however conditions have to be right. There has to be plenty of humidity in the air, and temperatures can’t be too low. According to Kevin Collins, president of Tsunami Products, the unit is ideal for areas within 10 to 15 degrees either side of the equator. “If you’re in the Los Angeles area, San Francisco, or San Diego, those areas have climates that typically don’t freeze,” says Collins, adding “…we can make water at anything above 50 degrees Fahrenheit.”

Can Existing AC Be Optimized for This?

Given the huge cost, it’s unsurprising that this technology is not yet mainstream. Tsunami Products reportedly sold just 20 units in 18 months prior to coverage by AP News. Since then, the company has reported a torrent of interest, and hopes to close on 50 orders by year’s end. Given the anxieties created by drought, it’s perhaps unsurprising that those with the means are jumping at the chance to secure their own water supply.

It does, however, raise the idea that perhaps the technology could be used in a more sustainable fashion. Anyone that’s seen water dripping off an air conditioner unit will be familiar with the principles at play. There’s perhaps scope to investigate capturing condensation from large air conditioning units in commercial and industrial installations, where it could be purified for use on-site. This could potentially reduce water use without increasing power usage, as it relies on the existing air conditioning system as it’s already employed. It’s something unlikely to work on the smaller home scale, due to the lower amounts of water such a system would harvest. However, for larger installations, it could prove beneficial.

Overall, however, water production from humid air remains an energy-intensive, and thus costly, exercise. While atmospheric water capture may find some applications in off-grid areas and with cashed-up homeowners, it’s in no way likely to serve as a widespread solution to the water woes of California and other drought-stricken areas. More traditional methods of saving and capturing water will have to be employed.